Meet the 2020 Judging Panel

The Nikon Small World Judging was conducted virtually for the first time in the history of the Competition.

Posted on September 10, 2020

The ultimate goal of the Nikon Small World competition is to share the best microscopic images and videos of the year with the public. Each year, the Nikon Small World team assembles a panel of expert judges whose role it is to select the very best of the thousands of images and videos that are submitted to the competition. Nikon strives to select a panel whose expertise is both deep and varied - a team who can look at an image or video and understand the technical challenges of capturing the shot, the scientific significance, the aesthetic appeal, and the power of conveying a story to the viewer. The panel is also tasked with identifying the microscopy that does the best job of sparking curiosity, conveying important research, or blending artistic vision with the latest innovations in science and technology

In this article, you’ll meet the members of the 2020 judging panel who lent their expertise and opinions (virtually, for the first time in the competition’s history) to evaluate and choose which of this year’s submissions would make it to the winner’s circle.

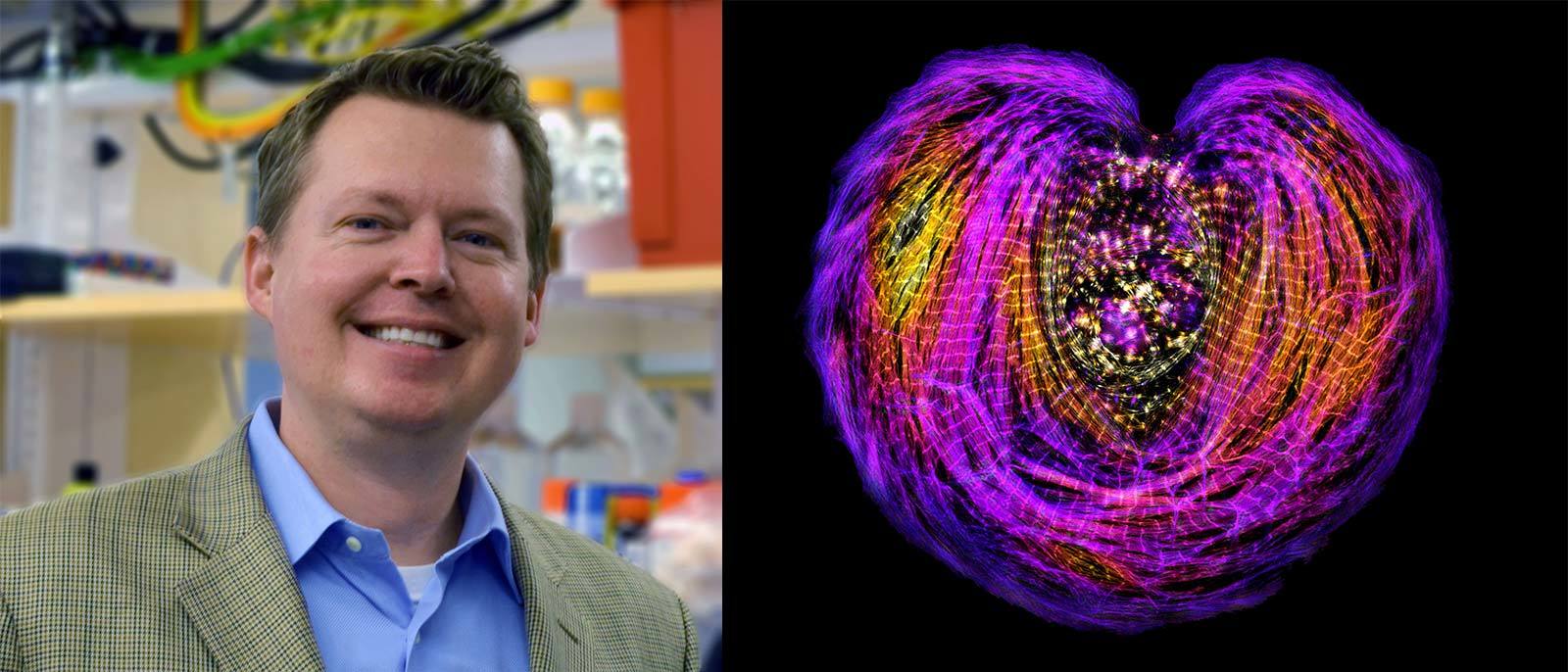

Dr. Dylan Burnette

Dr. Burnette is a familiar name for longtime fans of Nikon Small World. Burnette has placed in the competition 11 times and is known for his ability to capture images and videos of single cells under the microscope. Now an Assistant Professor of Cell and Developmental Biology at Vanderbilt University, he has used microscopy to observe cells since he was a junior in college at the University of Georgia. The very same year, he found his passion in cell biology. Today, Burnette’s lab is focused on studying how cells both enlarge and divide to eventually create full grown organs. Burnette is particularly interested in how the muscle tissue of the heart grows.

"The heart is particularly interesting because the method in which it typically grows during our lifetime is by the cells enlarging - the cells don’t typically divide.” According to Burnette, this can be dangerous for human health when the cells enlarge too much, which can cause a host of cardiovascular diseases. It can also affect healing and recovery from heart events. For example, when a person experiences a heart attack (i.e., myocardial infarction), the cells cannot divide and regrow. By studying the way cells grow to create heart muscle, Burnette’s lab hopes to gain a better understanding of the heart, leading to better diagnoses and treatments of heart-related illnesses.

_____________________________________________

Samantha Clark

A visual storytelling ability and a keen eye for what will spark curiosity in a person viewing a picture plays a pivotal role in how the panel selects our winners. Samantha Clark provides that skill set in surplus. Starting school as a pre-nursing major, Clark took a journalism class early on in her college career to learn how to make a food blog she ran as a hobby more compelling. As she says, “the rest is history.”

Today, Clark is a photo editor focusing on science stories at National Geographic, where she commissions and curates photography for both the magazine and natgeo.com. Previously, she worked at local newspapers and in public radio at NPR, KQED, and KAZU. She started her career as a writer but fell in love with visual storytelling while collaborating with photographers.

“The still image has the power to make us pause, giving us time to better understand,” Clark said. “Because of that, photography is a great way to make science more accessible and to promote scientific literacy.”

Every day at National Geographic, Clark edits photographs from all corners of science, from physics to paleontology, from space exploration to environmental degradation here on Earth. “One of my main goals as a science editor is to get people to care about science through photography,” she said. “I want to pull them into a story with amazing photos, and then hold their attention with a great visual narrative.”

That is always the challenge. Photography is an art, not a science. For her, there is no formula for making a great picture. “There are so many technically good photos in the world, but the best ones seduce you,” she said. “Does it surprise you? Does it draw you in emotionally? Does it make you feel something?” Clark said she is always looking for new photographers and new ways of looking at the world.

_____________________________________________

Dr. Christophe Leterrier

Dr. Christophe Leterrier started his career as an engineer but was eventually drawn to the study of neurons. He had a passion for technology but also for the dynamics of living things, so studying these tiny nerve cells using complex machines was a chance to work with both. Today, Leterrier works as group leader at the Institute of Neurophysiopathology at CNRS and Aix-Marseille University, where his team studies and observes neurons and their development using advanced microscopy techniques. For Leterrier, it does not hurt that the neurons create beautiful images.

“I have been studying the subcellular organization of neurons for years, using the cultured neurons model that I have fallen in love with for its ability to access the molecular details of cells, but also for the beauty of its images.” Leterrier has a special appreciation for microscopy and scientific imagery, particularly because it helps the public to understand some of the more complex research scientists like himself do every day.

“Getting people interested in our fundamental scientific question is not easy: people have complicated lives, plenty of things to do, they think it's too abstract or esoteric. But when you see something beautiful you spontaneously stop and want to know more - they say ‘hey, what is this, it's beautiful!’ so the beauty of microscope images are a great gateway to introducing the science behind it.”

If Leterrier had to share one piece of advice for budding microscopists, he’d say not to get too hung up on having the most complex or newest equipment, “Microscopes are precision machines and most of them, even the basic ones, can make incredible images. You must spend time on it, explore its possibilities, and adapt your sample preparation to make the most out of it. So, my advice would be to spend time at the microscope, read the manual front to cover, understand how it works, experiment, and try to make each image a bit better than the previous one.”

_____________________________________________

Sean Greene

Turning numbers and hard data into compelling visuals that the public can understand is no easy feat, and it’s a skill that translates well into interpreting which scientific visuals will resonate with a broad audience. As a graphics and data journalist covering science, the environment and medicine at The Los Angeles times, Sean Greene is an expert in doing just that. While he started out his career in more traditional forms of journalism, Greene was drawn to the way a multi-media spin could bring a story to life.

According to Greene, “A strong visual is what gets people’s attention so that we can tell important stories – especially in the digital age and within scientific communication. My work focuses on how to combine text, videos, and images so that each becomes greater than the sum of its parts. I help them build on each other in a way that creates an experience or helps the reader understand what they are looking at in a way that text alone couldn’t do.”

From the time Greene was young, he was particularly interested in science and nature. “As a camp counselor, I loved chasing bugs, identifying plants and exploring nature. I still spend as much time outdoors as I can. I wanted a career that would allow me to explore the natural world. Visuals-based science journalism lets me do that.” Scientific imagery and microscopy are particularly compelling, because as Greene says, “the images transport you to an unseen world. Or maybe it is something we are familiar with but are seeing from a different perspective. A lot of us have swam in a lake or an ocean, but we forget there’s a whole universe of creatures in that water around us, and that universe is vibrant.”

Currently, Greene is working on creating data-driven stories for Californians that help them to understand the impact of COVID-19 on their communities. He is always looking for his next story on oceanography or citizen science.

_____________________________________________

Ariel Waldman

Like many who enter the Nikon Small World competition, Ariel Waldman had a unique path to becoming a microscopy connoisseur. An art school graduate, Waldman loved creativity and connecting with people, but also had a desire for adventure and scientific discovery that could not be stifled. After accepting a job at NASA as program coordinator - a role that had Waldman facilitate collaboration between groups in and outside of NASA, Waldman found her passion: finding ways to connect science with art and helping those with non-traditional career paths fall in love with scientific research.

“I found microscopy because I had thought to myself, where can I go that’s kind of like space? I realized microscopy could let me explore new worlds, and I could help photograph things that a lot of people don’t usually get to see,” Waldman said.

Waldman wanted to delve deeper into the science world and took a course in microscopy so that she could be an asset to researchers in the field. Earning her stripes as an on-site microscopist, Waldman’s insatiable curiosity eventually led her to Antarctica, where she helped capture imagery of the tiny creatures living under the ice.

Microscopy, Waldman says, is particularly special because, “Microscopy does not have to section out people. Anyone can learn how to do it. Sometimes science really excludes people – but by having microscopy – you can use it as a researcher, as an artist, or a scientist – it can be inclusive of so many other people – it allows for more diversity of thought, it’s a discipline where you don’t just have to be one thing.”

To stay up to date with Nikon Small World, follow us on Instagram, Twitter, and Facebook. Be sure to follow Nikon Instruments for the latest updates on equipment and technology.