Nikon’s Small World competition has showcased the world’s most compelling microscopy images — and the most talented artists and scientists who captured them — for over four decades. Thousands of remarkable images are submitted by hundreds of entrants year over year, and each year we proudly share new talent with the world.

That said, certain individuals have seen their stunning imagery win a top spot again and again thanks to work that enthralls competition judges and fans alike. One of those individuals, and one of Nikon Small World’s most prolific winners is Wim van Egmond.

Beginning in 2002, his images have been recognized by Nikon Small World 32 times, including two first place finishes and a total of 10 top twenty finishes.

Based in the Netherlands, Van Egmond lives at the exact spot where Antoni van Leeuwenhoek in 1674 found microbes for the first time. A fan of Leeuwenhoek’s work, Van Egmond set out to learn more about his discoveries and developed a passion for capturing photos through the microscope.

His photos and videos span many subjects, but Van Egmond has an impressive talent for capturing microscopic life forms, such as diatoms, ciliates and rotifers. These living subjects can be quite difficult to capture, as they are sensitive to temperature changes and tend to retract because of the heat of the microscope illumination lamp. Aside from being fragile living beings, it is almost impossible to know when an exciting moment is about to happen under the microscope. Without patience and a careful eye, it would have been very easy to miss the shot that won him the 2015 Small World in Motion prize, a Trachelius ciliate finding its dinner in a Campanella ciliate.

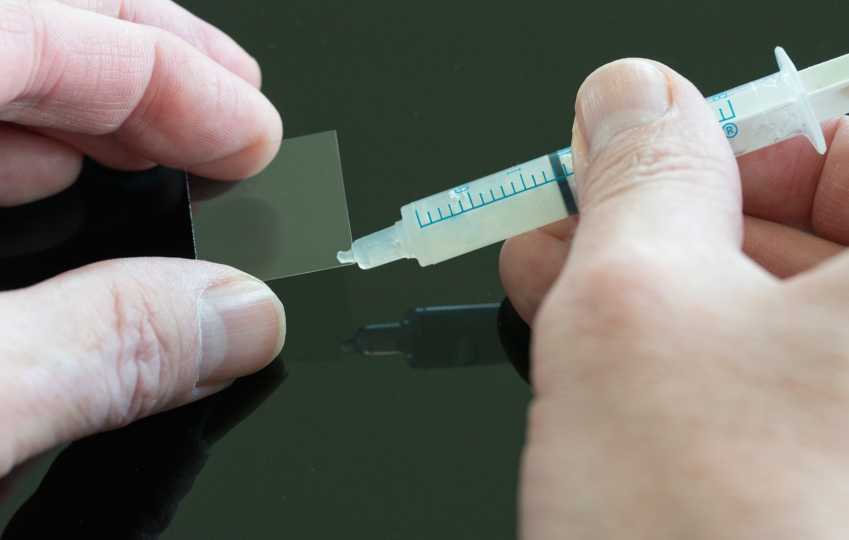

Van Egmond is by training and trade, not a scientist but an artist and photographer. As someone who does not have access to a high-tech lab every day, a unique aspect of Van Egmond’s work is his innovative approach to the preparation of his images. While science labs use various advanced sample preparation techniques, he uses a combination of traditional tools and a few DIY techniques. For example, rather than high precision sample manipulation equipment, he’s used a cat’s whiskers (that fell off his pet cat naturally) to properly position a mud dwelling microbe. He also uses a common household item, Vaseline, to support the cover slip over his subjects and prevent it from moving and damaging his sensitive subjects. He used this method for the image of the diatom that won in 2013.

Van Egmond explains, “What probably no one realizes is that this diatom is as deep as it is high and very fragile. It is a cork screw and the spines extend outwards around it. So the slide itself must be just deep enough so that the subject would be touching the coverslip without being damaged.”