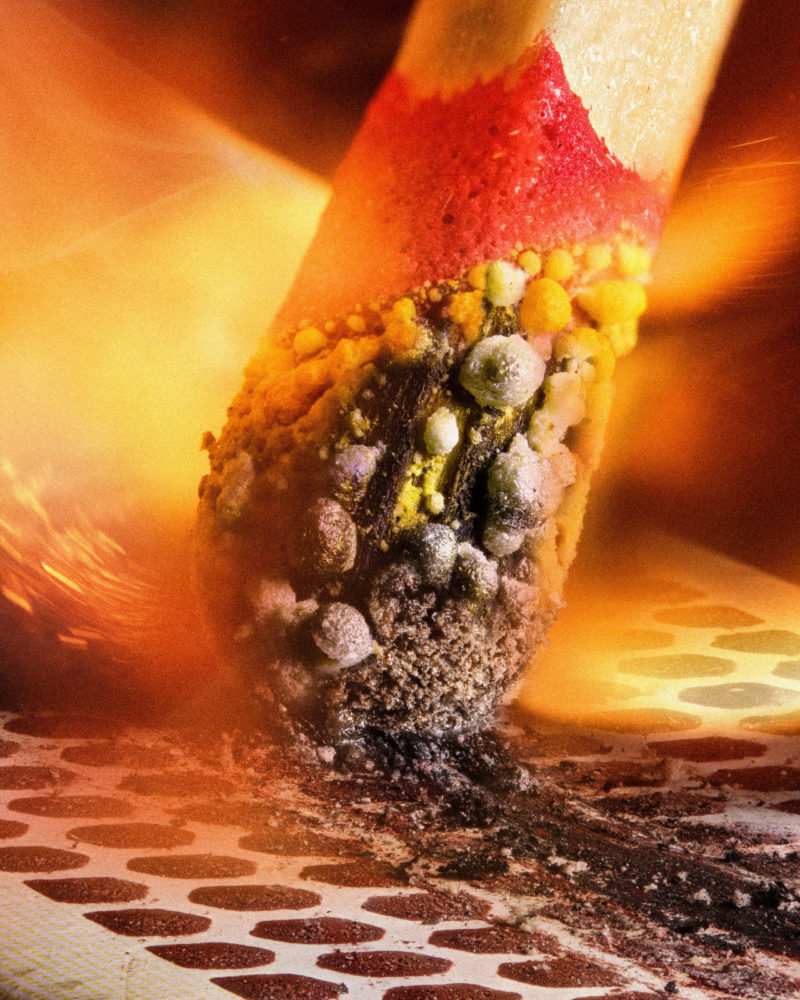

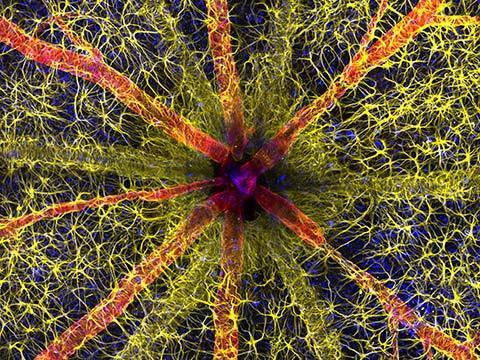

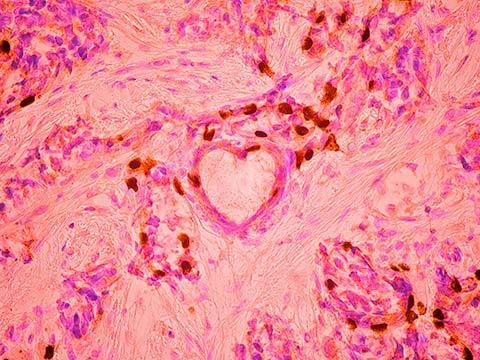

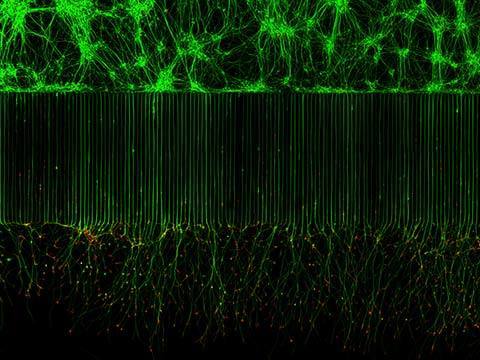

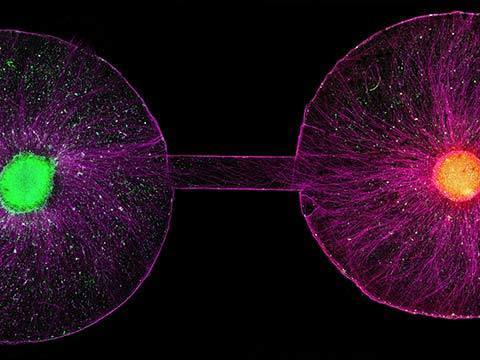

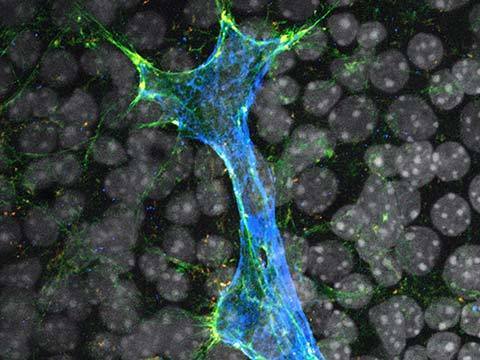

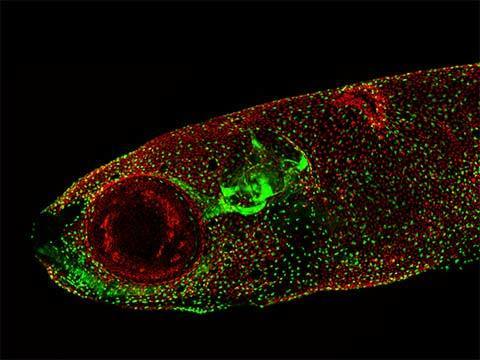

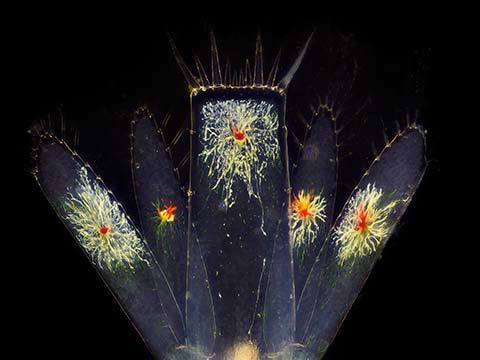

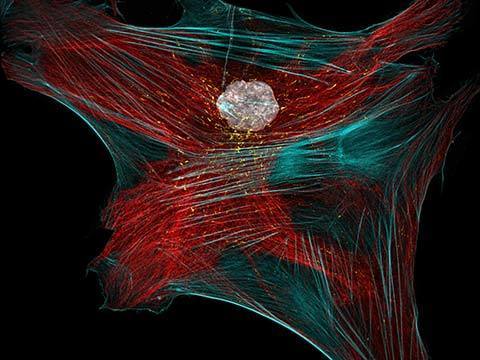

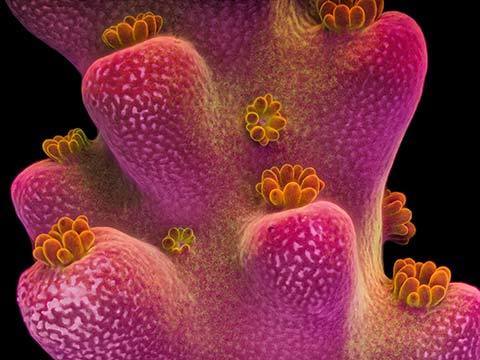

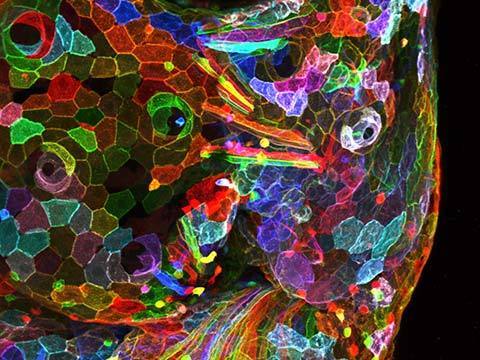

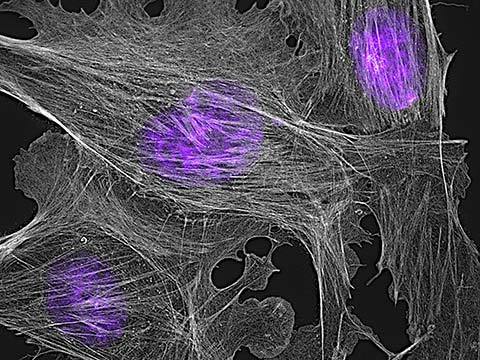

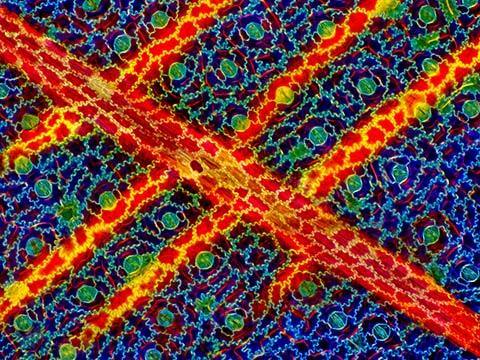

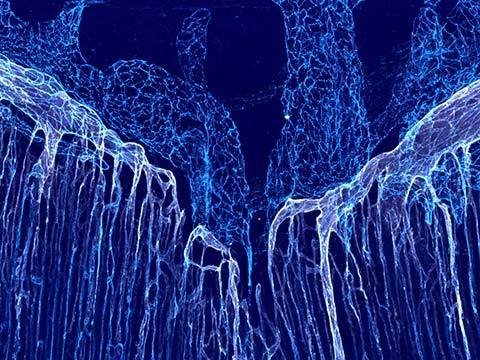

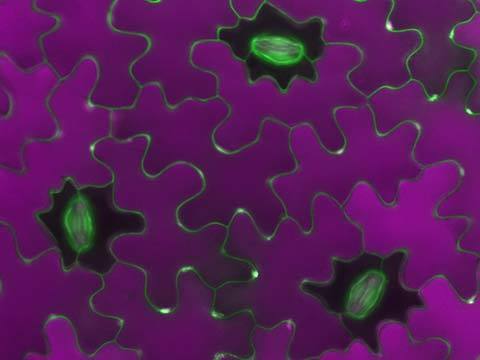

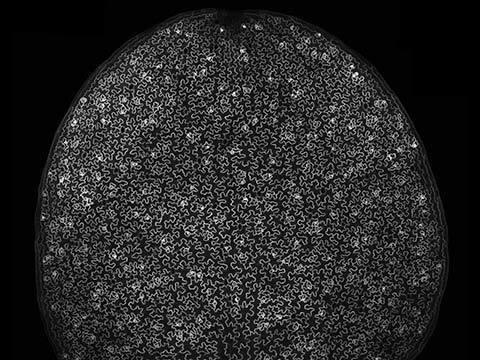

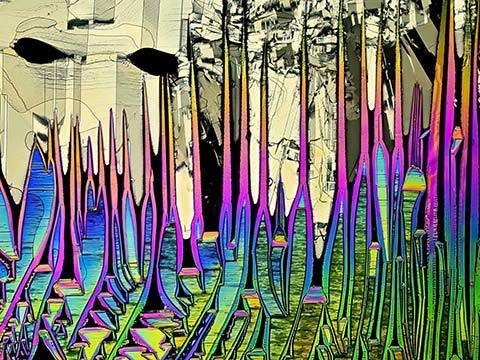

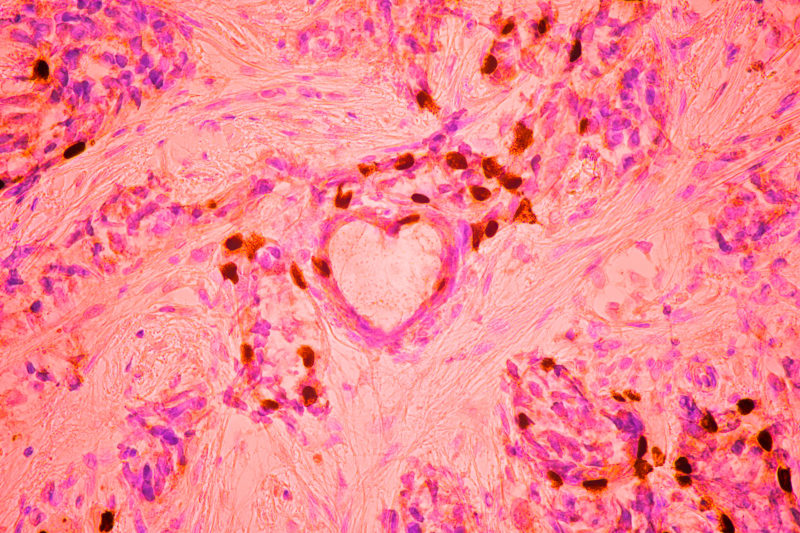

October is Breast Cancer Awareness Month in the United States. To recognize the more than 360,000 people who will be diagnosed with breast cancer in 2024, Nikon Instruments conducted an interview with previous Small World winner Malgorzata Lisowska. Lisowska’s captivating image of her breast cancer cells forming the shape of a heart earned her third place in the 2023 Nikon Small World competition. The image serves not only as a remarkable scientific accomplishment but also as a powerful symbol of hope and beauty in the face of adversity.

In this interview, Malgorzata Lisowska shares her personal journey as a healthcare advocate to then becoming a cancer patient herself, describing how her diagnosis of triple-negative breast cancer in early 2023 inspired her to turn the lens on her own cells. Through her photography, Lisowska aims to reshape the cancer narrative, using the art of microscopy to bring new depth and understanding to patient experiences and public awareness.

Share

Share Tweet

Tweet Pin-It

Pin-It