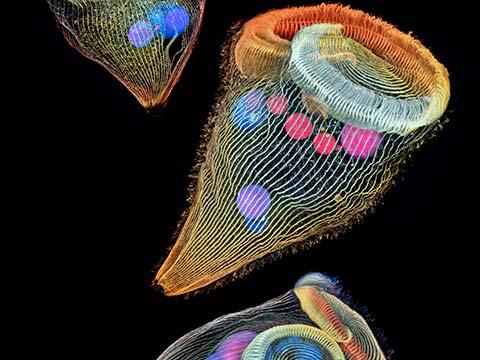

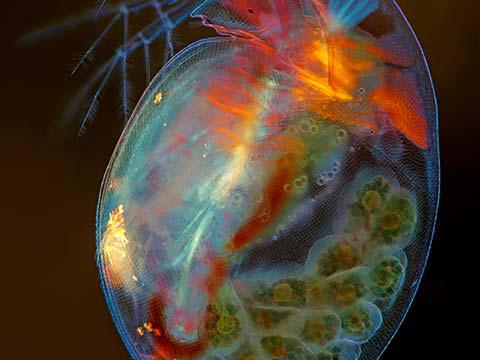

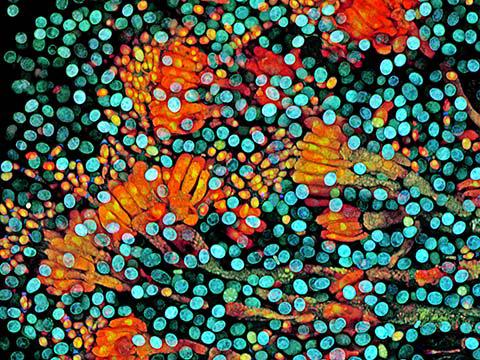

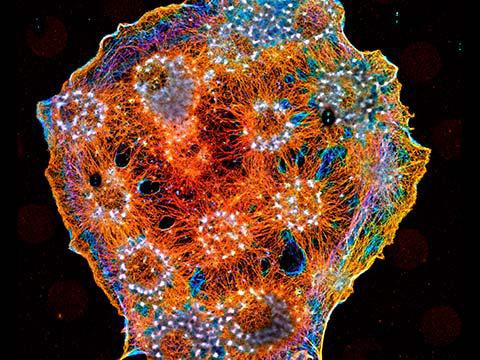

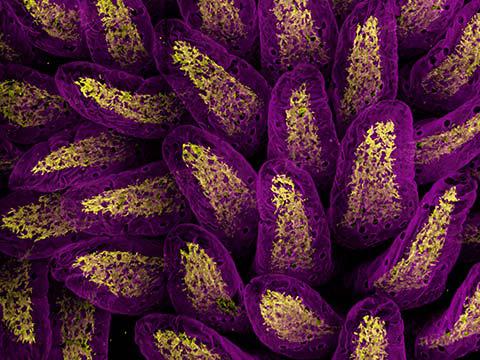

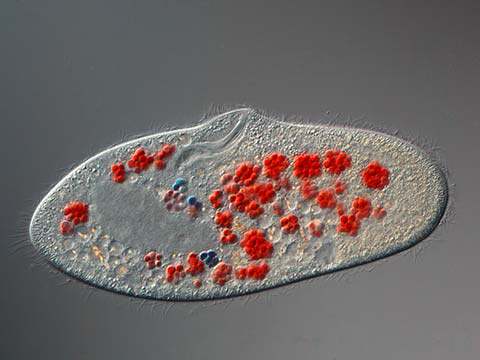

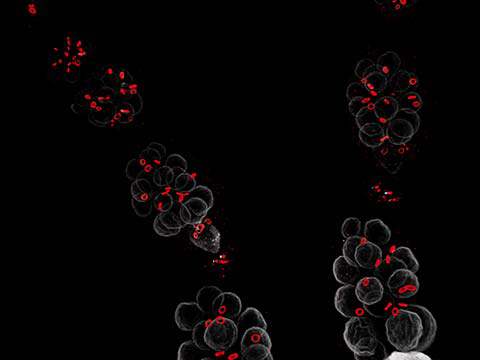

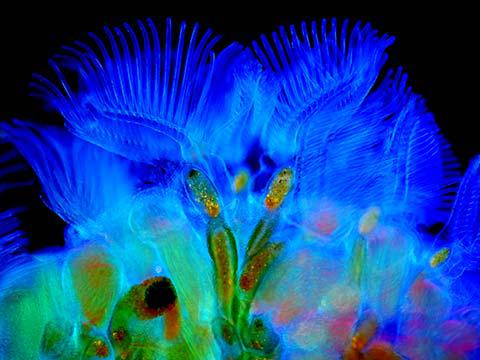

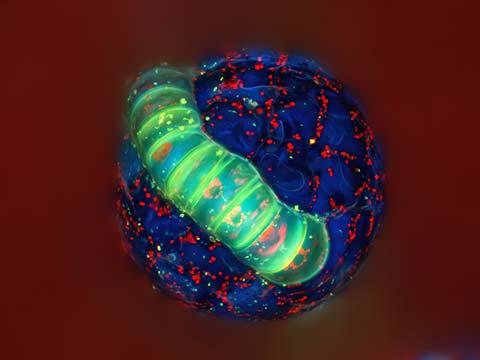

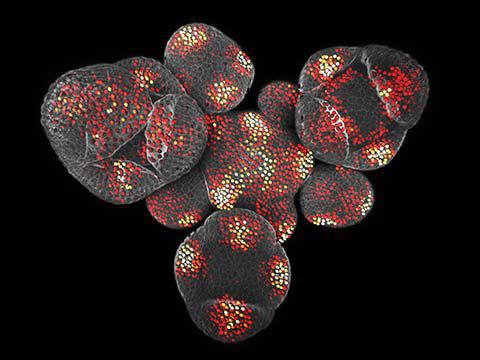

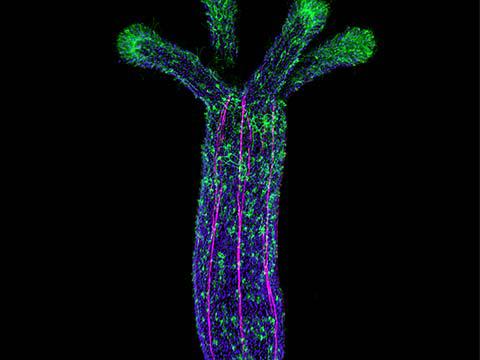

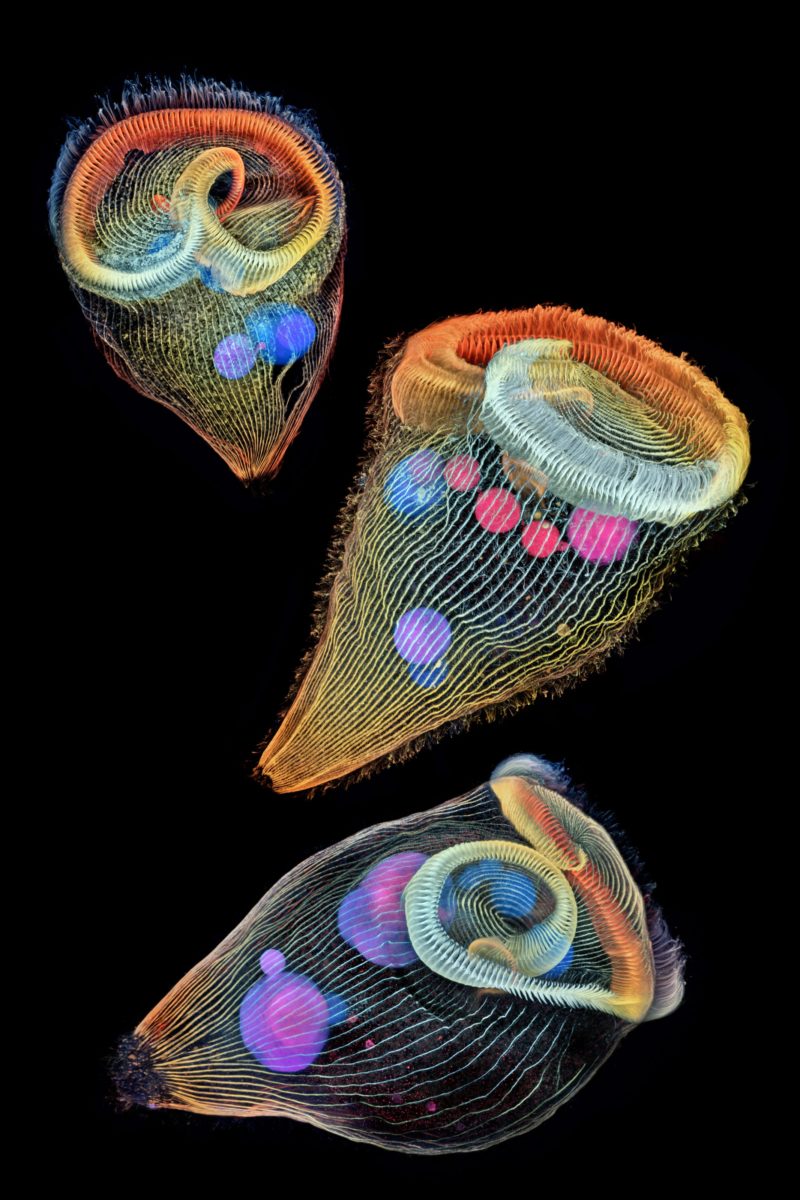

Nikon Small World veteran Dr. Igor Siwanowicz took second place in the 2019 Photomicrography Competition for his composite image of three single-cell freshwater protozoans, sometimes called "trumpet animalcules.” He used confocal microscopy to capture the detail of the cilia, tiny hairs used by the animals for feeding and locomotion.

2019 Photomicrography Competition

Top 20

Honorable Mentions

Images of Distinction

Judges

Dr. Denisa Wagner

Edwin Cohn Professor of Pediatrics at Harvard Medical School and the Head of the Wagner Lab Harvard Medical School and Boston Children’s Hospital

Dr. Wagner has dedicated her career to the fields of vascular cell biology and the causes of inflammation and blood clots. For many years, her laboratory’s research has focused on adhesion molecules (cell adhesion molecules help cells stick to each other and to their surroundings) and their function in normal physiology and in pathological situations. One of her labs’ current interests is the biology of neutrophil extracellular traps (networks of extracellular nuclear DNA) and the study of their production using time-lapse microscopy.

Dr. Rita Strack

Senior Editor Nature Methods

Dr. Strack has been an editor at Nature Methods since November of 2014. Her primary areas of coverage for the journal are imaging, microscopy, and probes, but her interests and expertise also extends to molecular biology, structural biology, and biophysics. She attended the University of Chicago, where she earned her Ph.D. in Biochemistry in 2010. Strack did a postdoctoral fellowship at Weill Cornell College of Medicine, where she spent countless hours on the microscope getting beautiful images to better understand the toxic RNAs associated with Fragile-X tremor, an adult-onset neurodegenerative disease.

Tom Hale

Staff Writer IFLScience

Hale is a London-based journalist at beloved popular science publication IFLScience. He is an experienced science writer, researching and sharing insights on everything from new species and biomedical breakthroughs to climate change and viruses. He has also written on art in culture, his work appearing in publications such as VICE’s Motherboard and FACT Magazine.

Ben Guarino

Science Reporter The Washington Post

A top science writer for The Washington Post, Guarino focuses on the practice and culture of science. Before making the switch to journalism, Guarino studied bioengineering and worked at the Spine Pain Research Lab at the University of Pennsylvania. He has also worked as a freelance science journalist, an associate editor at the Dodo and a medical reporter at the McMahon Group. His work has also appeared in publications like The Verge and The Huffington Post.

Share

Share Tweet

Tweet Pin-It

Pin-It